Johnny Griffin

Griffin was known as a brilliant technician, a fiery player who had an endless supply of chops. In 1960 he formed a ‘tough tenor’ band with Eddie “ Lockjaw” Davis, with an in your face approach. Though small in stature, Griffin has always been a musical mercenary willing to back up his reputation at any time, anyplace, anywhere.

Griffin was known as a brilliant technician, a fiery player who had an endless supply of chops. In 1960 he formed a ‘tough tenor’ band with Eddie “ Lockjaw” Davis, with an in your face approach. Though small in stature, Griffin has always been a musical mercenary willing to back up his reputation at any time, anyplace, anywhere.

But there has always been underlying warmth, a blues-based sense of everyday humanity, in his music. He is an amazingly consistent soloist, a man who is never off form by all accounts; undeniably he likes fast tempos but is a complete, rounded jazz musician, capable of tackling any material with the aid (or something otherwise!) of any rhythm section. He is still the model for tough tenors everywhere.

J. J. Johnson

J.J. Johnson made an indelible mark on the history of jazz when, with the help of Dizzy Gillespie, he reconfigured trombone playing for the be-bop era, playing linear progressions, minimizing vibrato, and producing a lucid, controlled, and clean sound which yet has the ability to express a wide range of emotions and musical ideas.

J.J. Johnson made an indelible mark on the history of jazz when, with the help of Dizzy Gillespie, he reconfigured trombone playing for the be-bop era, playing linear progressions, minimizing vibrato, and producing a lucid, controlled, and clean sound which yet has the ability to express a wide range of emotions and musical ideas.

Considered by many to be the finest jazz trombonist of all time, J.J. Johnson somehow transferred the innovations of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie to his more awkward instrument, playing with such speed and deceptive ease that at one time some listeners assumed he was playing valve (rather than slide) trombone.

J.J. Johnson is known to the listening public as a jazz trombonist who has repeatedly won the Downbeat and many other polls, who has played the instrument at super-rapid clips.

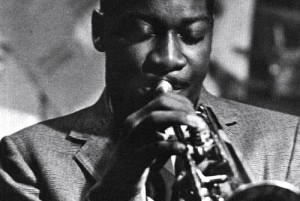

Fats Navarro

Navarro had a lyrical feeling to his playing to go along with his breathtaking technical facility and his high note ability which he used sparingly but with great effect. Navarro achieved considerable popularity with the jazz public and was highly admired by both critics and fellow musicians.

Navarro had a lyrical feeling to his playing to go along with his breathtaking technical facility and his high note ability which he used sparingly but with great effect. Navarro achieved considerable popularity with the jazz public and was highly admired by both critics and fellow musicians.

Navarro left a legacy of about 150 recorded sides of phenomenal consistent quality. In 1982, he was elected by the International Jazz Critics into the Down Beat Hall of Fame. He was a major influence on Clifford Brown and through him Navarro has indirectly influenced so many of the trumpeters playing today as Benny Bailey, Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Sam Noto and Woody Shaw.

Zoot Sims

He was, simply put, a hell-for-leather improviser who could out-swing any rival, whatever their instrument. Zoot never became a superstar like his onetime “brother” in the Woody Herman reed section, Stan Getz, nor was he a distinguished composer-orchestrator like his longtime partner Al Cohn. But this terror of a competitor could kick anyone’s rear end in a jam session, and you had to pity the fool who dared take him on.

He was, simply put, a hell-for-leather improviser who could out-swing any rival, whatever their instrument. Zoot never became a superstar like his onetime “brother” in the Woody Herman reed section, Stan Getz, nor was he a distinguished composer-orchestrator like his longtime partner Al Cohn. But this terror of a competitor could kick anyone’s rear end in a jam session, and you had to pity the fool who dared take him on.

Starting in his youth, saxophonist Zoot Sims fashioned his seemingly effortless sound from the music of early masters Lester Young and Ben Webster. Never a musician to chase trends, he always kept two classic jazz principles in mind: Always play with indomitable swing, and have faith in the infinite variety to be gleaned from a familiar set of chord changes.

Bobby Timmons

Pianist Bobby Timmons came out of Philadelphia at age 19, with a funky gospel tinged piano style, combined with hard bop and the blues to create a sound which dominated much of jazz during the late 1950s and early 1960s. He would, in a recording career that would only span a short time frame, contribute to some of the best recordings on the legendary Blue Note sessions of the ’50’s.

Pianist Bobby Timmons came out of Philadelphia at age 19, with a funky gospel tinged piano style, combined with hard bop and the blues to create a sound which dominated much of jazz during the late 1950s and early 1960s. He would, in a recording career that would only span a short time frame, contribute to some of the best recordings on the legendary Blue Note sessions of the ’50’s.

His musical resume for the period between 1956 and 1969 is very impressive. He was with Kenny Dorham and the Jazz Prophets in 1956, which also included Kenny Burrell on guitar. In the years ’56 through ’57 he was with Chet Baker. The year 1957 would be a very productive and busy one as he worked and recorded with Hank Mobely, Sonny Stitt, Lee Morgan, and Curtis Fuller. In the same year and into ’58 was in Maynard Fergusons’ band, and also did session dates with Art Pepper and Kenny Burrell.

Harold Land

Harold Land was an original voice in the crowded field of bop-inspired tenor saxophonists. He chose to spend most of his career in Los Angeles, where his sharp, hard-edged sound went against the perceived norm of the so-called cool sound associated with the west coast. He will be remembered particularly for his two year spell with the great band co-led by Clifford Brown and Max Roach, one of the seminal jazz groups of the mid-1950s, and his own classic albums, In The Land of Jazz and The Fox.

Harold Land was an original voice in the crowded field of bop-inspired tenor saxophonists. He chose to spend most of his career in Los Angeles, where his sharp, hard-edged sound went against the perceived norm of the so-called cool sound associated with the west coast. He will be remembered particularly for his two year spell with the great band co-led by Clifford Brown and Max Roach, one of the seminal jazz groups of the mid-1950s, and his own classic albums, In The Land of Jazz and The Fox.

Harold Land is an underrated tenor saxophonist whose tone hardened with time and whose improvising style after the 1960s became influenced by the innovations of John Coltrane, and his sound and approach changed quite radically for a time, adding further depth to his armoury.

Jaki Byard

Jaki Byard was one of jazz’s most idiosyncratic talents. A pianist capable of playing in almost any jazz style as well as a highly original creative voice, he contributed to epoch-making recordings with some of the most important names in Sixties jazz, such as Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and left a powerful legacy of his own work as a band leader and as an inspirational teacher.

Jaki Byard was one of jazz’s most idiosyncratic talents. A pianist capable of playing in almost any jazz style as well as a highly original creative voice, he contributed to epoch-making recordings with some of the most important names in Sixties jazz, such as Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and left a powerful legacy of his own work as a band leader and as an inspirational teacher.

His playing was rich, masterful and above all, versatile, covering everything from stride and ragtime to bebop and free jazz. Pianist, saxophonist, composer, arranger, and teacher Jaki Byard had a career that followed the music – along the way he became a master of every style of jazz.

Blue Mitchell

Trumpeter Blue Mitchell was best known as a highly lyrical and hard-swinging player, with accomplished craftsmanship and a clear tone. Owner of a direct, lightly swinging, somewhat plain-wrapped tone that fit right in with the Blue Note label’s hard bop ethos of the 1960s, Blue Mitchell tends to be overlooked today perhaps because he never really stood out vividly from the crowd, despite his undeniable talent.

Trumpeter Blue Mitchell was best known as a highly lyrical and hard-swinging player, with accomplished craftsmanship and a clear tone. Owner of a direct, lightly swinging, somewhat plain-wrapped tone that fit right in with the Blue Note label’s hard bop ethos of the 1960s, Blue Mitchell tends to be overlooked today perhaps because he never really stood out vividly from the crowd, despite his undeniable talent.

Blue Mitchell made his name as a member of Horace Silver’s quintet, where his lyrical playing and beautiful timbre perfectly complemented Silver’s simplified, soulful brand of bop. Mitchell later developed into a trumpeter and bandleader who produced jazz that was ultimately infectious, fully flavored with soul and swing, but devoid of all pretentiousness.

Don Byas

Byas was a masterful swing player with his own style, an advanced sense of harmony, and a confidence that was unmistakably his own, immediately recognizable. His sense of drama coupled with a brilliant use of dynamics and timbre, a deeply-felt romanticism – accomplished both the tenderest warmth and the most strident sting. He never picked up the rhythmic phrases, the lightning triplets, that are indigenous to bop. Yet Charlie Parker said of him that Byas was playing everything there was to play.

Byas was a masterful swing player with his own style, an advanced sense of harmony, and a confidence that was unmistakably his own, immediately recognizable. His sense of drama coupled with a brilliant use of dynamics and timbre, a deeply-felt romanticism – accomplished both the tenderest warmth and the most strident sting. He never picked up the rhythmic phrases, the lightning triplets, that are indigenous to bop. Yet Charlie Parker said of him that Byas was playing everything there was to play.

One of the greatest of all tenor players, Don Byas’ decision to move permanently to Europe in 1946 resulted in him being vastly underrated in jazz history books. His knowledge of chords rivalled Coleman Hawkins, and, due to their similarity in tones, Byas can be considered an extension of the elder tenor.

Horace Parlan

Pianist and composer Horace Parlan over his 50 year career has recorded 30 albums as a leader and has been a sideman with many jazz greats, overcoming physical disability and thrived as a pianist despite it. His right hand was partially disabled by polio in his childhood, but Parlan made frenetic, highly rhythmic right hand phrases part of his characteristic style, contrasting them with striking left-hand chords.

Pianist and composer Horace Parlan over his 50 year career has recorded 30 albums as a leader and has been a sideman with many jazz greats, overcoming physical disability and thrived as a pianist despite it. His right hand was partially disabled by polio in his childhood, but Parlan made frenetic, highly rhythmic right hand phrases part of his characteristic style, contrasting them with striking left-hand chords.

Much of pianist Horace Parlan’s distinguished jazz life has been marked by an intriguing series of ebbs and flows. At times his artistry has received the attention and praise it deserves, while at others it has been curiously overlooked and neglected. All the more interesting is that amid these sometimes unnerving shifts, Parlan has remained a model of musical consistency.

Curtis Fuller

In a career that has spanned over 60 years, dozens of recordings and countless gigs, Blue Note Records artist Curtis Fuller is widely acknowledged as one of the most influential and respected trombonists in the history of jazz.

In a career that has spanned over 60 years, dozens of recordings and countless gigs, Blue Note Records artist Curtis Fuller is widely acknowledged as one of the most influential and respected trombonists in the history of jazz.

Curtis Fuller has been a remarkable survivor, not to mention a consistent and versatile player throughout his entire career. Fuller is his own man. His melodic ideas are inventive and immaculately executed, with a fast and definitive articulation. His assured tone and intonation is equally capable of a burnished glow and flashy brilliance. Fuller has the capability to stay within his limits, managing to blend with his front line mates while contributing solos that could hold their own, even in the company of a John Coltrane.

Eric Dolphy

Dolphy was one of several groundbreaking jazz alto players to rise to prominence in the 1960s. He was also the first important bass clarinet soloist in jazz, and among the earliest significant flute soloists; he is arguably the greatest jazz improviser on either instrument. His improvisational style was characterized by a near volcanic flow of ideas, utilizing wide intervals based largely on the 12-tone scale, in addition to using an array of false fingerings to create a multiphonic effect which almost made his instruments speak.

Dolphy was one of several groundbreaking jazz alto players to rise to prominence in the 1960s. He was also the first important bass clarinet soloist in jazz, and among the earliest significant flute soloists; he is arguably the greatest jazz improviser on either instrument. His improvisational style was characterized by a near volcanic flow of ideas, utilizing wide intervals based largely on the 12-tone scale, in addition to using an array of false fingerings to create a multiphonic effect which almost made his instruments speak.

Although Dolphy’s work is sometimes classified as free jazz, his compositions and solos had a logic uncharacteristic of many other free jazz musicians of the day; even as such, he was definitively avant-garde. In the years after his death his music was more aptly described as being “too out to be in and too in to be out.”

Philly Joe Jones

Philly Joe Jones is one of the greatest of the hard boppers. His contributions to the art of jazz drumming are immeasurable. He was a virtuoso with a pair of brushes, and a genius at turning the rudiments into fluent musical ideas. More than any of his peers, it was Philly Joe’s time feel that defined the idea of swing in the 1950s. In retrospect, he would prove to be the strongest link in the chain between Max Roach, Art Blakey, and Roy Haynes, and the Elvin Jones/Tony Williams school that was soon to emerge.

Philly Joe Jones is one of the greatest of the hard boppers. His contributions to the art of jazz drumming are immeasurable. He was a virtuoso with a pair of brushes, and a genius at turning the rudiments into fluent musical ideas. More than any of his peers, it was Philly Joe’s time feel that defined the idea of swing in the 1950s. In retrospect, he would prove to be the strongest link in the chain between Max Roach, Art Blakey, and Roy Haynes, and the Elvin Jones/Tony Williams school that was soon to emerge.

The volume, aggressiveness, and explosiveness of Jones’ playing and the subtlety of his cross-rhythms helped to expand the role of the drums in jazz. A superb timekeeper, he was known especially for his technique with brushes, as well as his cymbal playing and his carefully structured solos.

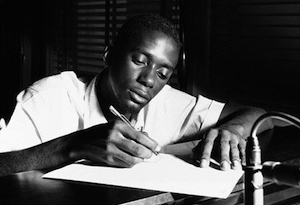

Tadd Dameron

Tadd Dameron as a composer and arranger was the man who in the 1940s and ‘50s was among the first to use the sometimes raw and undisciplined devices of the then- new style of jazz called bebop in well-developed arrangements for big bands and small groups. Perhaps more than any other musician, Dameron added form to the then-emerging style of bop.

Tadd Dameron as a composer and arranger was the man who in the 1940s and ‘50s was among the first to use the sometimes raw and undisciplined devices of the then- new style of jazz called bebop in well-developed arrangements for big bands and small groups. Perhaps more than any other musician, Dameron added form to the then-emerging style of bop.

He began experimenting with new ideas while writing arrangements for the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra. Dameron recalled, “I started writing in my own style when I got on Count Basie’s band.” Arranging for Gillespie’s big band, Dameron took the long phrases, powerful upbeat rhythms and chord changes of bop that Dizzy and Charlie Parker were pioneering, and used them in big band arrangements.

Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis

Eddie Lockjaw Davis was one musician who provided a link from the big band era through to the soul jazz phenomenon of the late 1950′s and early 1960′s. Davis developed one of the most unmistakable tenor sax sounds in post war jazz, with a full bodied yet reedy tone that was equally at home in rhythm & blues settings as more modern contexts.

Eddie Lockjaw Davis was one musician who provided a link from the big band era through to the soul jazz phenomenon of the late 1950′s and early 1960′s. Davis developed one of the most unmistakable tenor sax sounds in post war jazz, with a full bodied yet reedy tone that was equally at home in rhythm & blues settings as more modern contexts.

His playing always had a direct, singing quality that was a huge influence on the next generation of sax men. Jaws was a blustery soloist who came to prominence in the world of Jazz at a time when you had to “make your bones” by engaging in “cutting” sessions with other tenor saxophonists. Such “duels” might include only another tenor sax player, or perhaps two others or even a stage full of them; some were known to go on all night, ending in the wee small hours of the morning.

Booker Little

Little had a memorable melancholy sound, featuring crisp articulation, and his interval jumps looked toward the avant-garde, but he also swung like a hard bopper. He was capable of stringing together beautifully shaped, swinging lines – but he was less confined to conventional bop phrasing and accentual patterns than his peers, and he often broke free from diatonicism and the blues.

Little had a memorable melancholy sound, featuring crisp articulation, and his interval jumps looked toward the avant-garde, but he also swung like a hard bopper. He was capable of stringing together beautifully shaped, swinging lines – but he was less confined to conventional bop phrasing and accentual patterns than his peers, and he often broke free from diatonicism and the blues.

Little focused his attention on intervallic relationships, overt harmonic extension and dissonance. His playing was angular and at times rigid, and he used wide intervallic leaps, with unexpected long notes in the middle of phrases, and a pulling-against-the-pulse technique, to create dramatic effects. Endowed with a magician’s ear, Booker Little’s innate lyricism and unwavering consistency of tone made ambitious and difficult improvisations sound easy.

Hampton Hawes

Hampton was famous for his prodigious right hand, his deep groove, his very personal playing, his profound blues conceptions, and his versatility within a mainstream context. He remained anchored in chord-change based jazz with chord changes his whole career. A direct descendant of bebop who had been variously classified as “West Coast” and “funk-jazz” or “rhythm school,” Hawes transcended all these categories.

Hampton was famous for his prodigious right hand, his deep groove, his very personal playing, his profound blues conceptions, and his versatility within a mainstream context. He remained anchored in chord-change based jazz with chord changes his whole career. A direct descendant of bebop who had been variously classified as “West Coast” and “funk-jazz” or “rhythm school,” Hawes transcended all these categories.

When Hawes tore into his solos, it was as if the piano had a life of its own; it was a performance that scorched. Hawes was a master at constructing solos beginning with a phrase and gradually building, drawing the listener in. When he reached the peak of his energy he was at a level few outside of Bud Powell could approach. A mostly self-taught musician, he matured early musically and late personally-by his own admission.

Paul Gonsalves

Gonsalves joined Duke Ellington in 1950 and stayed with him almost continuously for twenty-four years. He flirted with atonality long before John Coltrane or Eric Dolphy. In fact, his combination of cool atonality with hot rhythms made him one of the most original of all tenor sax men.

Gonsalves joined Duke Ellington in 1950 and stayed with him almost continuously for twenty-four years. He flirted with atonality long before John Coltrane or Eric Dolphy. In fact, his combination of cool atonality with hot rhythms made him one of the most original of all tenor sax men.

During his long, fragmented tenure with Ellington, Gonsalves became a giant. His playing bore traces of Webster and Hawkins, and, in more reflective moments, displayed what has been described as a ‘vocalsied but fragile tone’ reminiscent of Lester Young’s. Yet for all these borrowings, his became a distinctive, striking voice quite unlike those of the three grand masters and hardly ever their inferior. He was a giant of jazz, an engaging and delightful figure, and left behind on record, an extensive library of masterful musicianship.

Red Rodney

Red Rodney was a dynamic and creative player, displaying inventiveness and thorough mastery of his instrument in all bop and post-bop settings. Primarily known as Charlie Parker’s trumpet player, Red Rodney went on to become a legend himself and made several dramatic comebacks during his career to solidify his reputation as a bebop trumpeter and keeper of the flame.

Red Rodney was a dynamic and creative player, displaying inventiveness and thorough mastery of his instrument in all bop and post-bop settings. Primarily known as Charlie Parker’s trumpet player, Red Rodney went on to become a legend himself and made several dramatic comebacks during his career to solidify his reputation as a bebop trumpeter and keeper of the flame.

Rodney was a highly experienced big band trumpeter but was already experimenting with bebop. In 1949, with his reputation as a rising bop star fast gaining ground, he joined the Charlie Parker quintet (via an introduction from Dizzy Gillespie). For the next two years he was acclaimed as one of the best bebop trumpeters around and was certainly among the first white players to gain credibility and acceptance in the field.

Phineas Newborn Jr

Phineas Newborn Jr.’s technical command of the keyboard placed him alongside the greatest virtuosos of piano jazz, Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson. Newborn combined this raw skill with sensitivity and harmonic insights to create a style which continues to inspire admiration in every setting. One of the most technically skilled and brilliant pianists in jazz. Newborn’s bop-based style was largely unclassifiable, his technique was phenomenal, and he was very capable of enthralling an audience playing a full song with just his left hand or complex, and brisk solos with both hands in unison.

Phineas Newborn Jr.’s technical command of the keyboard placed him alongside the greatest virtuosos of piano jazz, Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson. Newborn combined this raw skill with sensitivity and harmonic insights to create a style which continues to inspire admiration in every setting. One of the most technically skilled and brilliant pianists in jazz. Newborn’s bop-based style was largely unclassifiable, his technique was phenomenal, and he was very capable of enthralling an audience playing a full song with just his left hand or complex, and brisk solos with both hands in unison.

Phineas demonstrates all the virtues and none of the handicaps inherent in knowing how to use the piano. Taking him on his own terms, he’s an involved, committed artist, for whom the instrument is an extension of the man.